By Jamie Zeman, DC

Chronic pain is a complex condition influencing behaviors, thoughts and mood. With opioid issues coming to light, there has been more emphasis and research into multi-faceted, biopsychosocial models to treatment. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a type of talk-therapy treatment that focuses on addressing and removing the negative impacts chronic pain has on thoughts and functions.2

The Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention (OMHSP) has implemented a national initiative to disseminate Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain throughout the Veterans Health Administration to make this treatment widely available to veterans. As part of this initiative, VA has developed a national training program in CBT-CP for Veterans with chronic pain.3

Through CBT, veterans learn strategies to address the negative emotions, thoughts and beliefs about their conditions as well as develop tools to respond to pain in healthier ways. Due to the complexity of chronic pain, patients can become frustrated and hopeless when they fail to respond to a variety of treatments, which in turn can further escalate emotions and symptoms. Through a course of individual or group sessions, the veteran learns to address the social, psychological and physical aspects of their condition. The goal of the treatment is to improve function and quality of life and give less focus to addressing pain intensity. The format of CBT within VA is typically an initial consultation with history and examination, followed by 10-12 weekly sessions of structured group format skills sessions and discussion.4

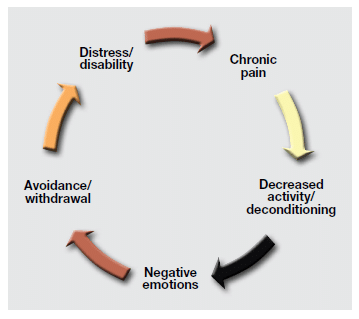

These weekly CBT sessions generally focus on practicing a specific skill, and then homework is handed out with tasks to be discussed at the next visit. The structuring and sequence of the treatment is designed to re-engage the patient in an active, problem-solving approach to living with chronic pain. Following the initial consultation, the treatment will typically begin with pain education and an overview of the program including introduction of the chronic pain cycle graphic (see graphic below) and making the connection between thoughts, actions, and emotions on pain perception. Goal setting is done early in the therapy plan, with focus on specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-based (SMART) goals and determining the focus and purpose of treatment while diverting attention away from pain.

Motivational interviewing may be used to help coach veterans into making changes in daily habits to accommodate these new activities. Veterans are guided through tasks and worksheets to help identify negative thoughts, increase awareness about these thoughts and their pain perception, and learn to challenge these ideas. Automatic negative thoughts (ANTs) such as “catastrophizing,” “all or none thinking,” “jumping to conclusions,” and “focusing on only bad events” are categorized and the veteran is tasked with coming up with positive replacements to these thoughts. Some common negative thoughts are “If I do this activity my pain with get to 10/10” or “Nothing will ever make this pain better” and “I have tried everything and nothing has worked.” As fatigue can increase pain sensitivity, factors that directly and indirectly affect sleep quality are recognized and education is provided on sleep hygiene. The program concludes with the veterans assessing their progress, writing their own continued coping strategy for exacerbations, and setting their next goals. The veteran may also return for a booster session to discuss application of coping skills and problem solving through life events that may have altered progress.4

Residency CBT-CP Rotation

It is my goal as a clinician in VA to improve self-management strategies among those with chronic pain by helping individuals improve their knowledge, skills, and confidence to prevent, reduce and cope with pain. I was fortunate to be provided with my own copy of the CBT-CP manual and complete an individualized informal education session with a psychologist who trains mental health care providers in the VA CBT protocol and manual. I learned that the biggest predictors for pain outcomes are psychosocial factors. While many studies have suggested that the biopsychosocial approach is the ideal for management of chronic conditions, the biological model is still prevalent in health care. Pain psychology is often a last resort for chronic pain treatment, despite clinical practice guidelines.5

I was also able to attend weekly sessions of a group cohort. I joined the group at the 6th session of a 10-week cycle. The cohort I joined has 6-10 regular attendees who actively participate. At each group, attendees have the option to introduce themselves, share their service background and discuss why they decided to join the CBT group. The group typically begins with discussing the previous week and how they utilized skills and handouts from the previous session to change behaviors. During sessions I have attended there has been discussion about catastrophizing, pacing, fear avoidance, goal setting and automatic negative thoughts. I have been very impressed with the quality of the materials and organization of the program. I have found joining the group to be very beneficial in determining when a referral is necessary and discussing these topics in my own practice. Though my time dedicated to talk-therapy is limited during chiropractic patient encounters, I have been able to incorporate elements on a daily basis. I found pacing to be a very helpful strategy when encouraging return to physical activity, especially when veterans present with fear avoidance. I now actively listen for automatic negative thoughts during history taking, and try to get the veterans to identify and challenge them. I have found that setting SMART goals have also been useful in identifying the specific areas in which chronic pain affects daily life, and useful in suggesting pleasant activities and determining functional goals of treatment.

Dr. Zeman is the current chiropractic resident at the Canandaigua VA Medical Center in Canandaigua, N.Y., working with program director Paul Dougherty, DC