Chiropractic integration into hospitals and other collaborative interdisciplinary environments remains aspirational for many recent graduates and seasoned providers alike; as the years have gone on, it has also become more commonplace [1]. Even for those chiropractors who don’t work directly in an integrated setting, many still co-manage and/or receive referrals from a variety of physicians and providers who are almost certainly providing medication management. This is especially relevant in the context of chronic pain. While many chiropractors may be able to reference the plethora of papers that link an inverse relationship between conservative non-pharmacologic treatment and prescription receipts (namely opioids, benzodiazepines, and gabapentin) [2-9], far fewer could probably tell you what evidence-based pharmacological management for chronic low back pain looks like.

This is likely reflective of the ever-evolving literature as well as the heterogeneity of prescribing practices between providers (not only primary care vs. emergency department provider, but also primary care provider A vs. primary care provider B). Of course, there is more than just reviewing the most recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) that goes into deciding what medication is appropriate for any given patient. Even when clinical practice guidelines, widely regarded as a gold standard of care, make recommendations, there are a variety of considerations such as the assumed risks outweighing the potential benefit, cost, accessibility, and follow-up [10].

A great example of this is providers and/or guidelines still recommending acetaminophen for low back pain, although a 2014 double-blind, randomized controlled trial in the Lancet with more than 1,100 patients found it to be no better than placebo for recovery time, pain, disability, function, global system change, sleep, and quality of life [11]. A 2016 Cochrane systematic review then underscored this by stating, “the high-quality evidence and precise estimate of no effect for acute low back pain suggest that no additional trials of paracetamol [acetaminophen] for acute low back pain are required.” Although providers recommending acetaminophen for low back pain continues.

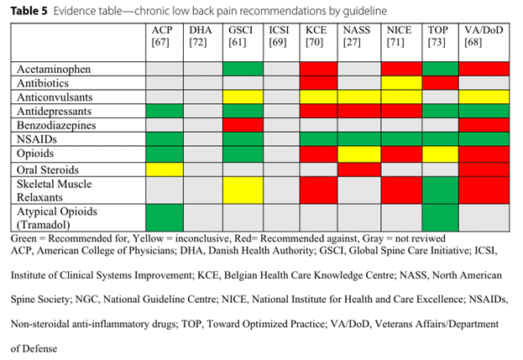

Below (table 5) is an excerpt from our recent systematic review, written by the non-prescribing provider for the non-prescribing provider to better address some of these differences [10]. The table reflects recent clinical practice guideline recommendations from around the globe for pharmacological management of chronic low back pain. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) were the most commonly endorsed medication, being recommended as a trial of care by all seven guidelines that reviewed the medication. Three guidelines specifically discussed ibuprofen, two discussed oral diclofenac, and one discussed naproxen, however six clinical practice guidelines did not recommend any specific NSAID. Ibuprofen dosage recommendations ranged from 1,200-1,800 mg per day to 2,400 per day, with a maximum of 3,200 mg per day [10]. It was underscored by multiple guidelines that taking NSAIDs were not without risk of adverse events and should be taken at the lowest effective dose for the shortest period of time. Potential risks included gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, renal, and/or hepatic concerns. Aside from NSAIDs, the remaining medication recommendations were widely heterogenous between clinical practice guidelines.

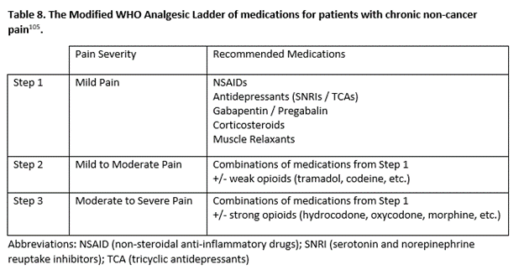

We may also compare these clinical practice guidelines recommendations with the World Health Organization’s Analgesic Ladder, which provider medication selection may also reflect (Table 8, an excerpt from another ongoing study of mine). The ladder was proposed in 1986 to address pain management in cancer care (later revised in 1996), but has been extrapolated to be utilized with non-cancer pain [13]. Utilization of the ladder begins with step one and providers are encouraged to only progress if patients continue to experience pain. This presents obvious challenges, not only in the context of chronic pain, but that some providers may assume that non-opioid and adjuvant analgesics pose no potential harm to patients.

Additionally, a recent systematic review for pharmacological management of chronic low back pain (>6 weeks) reviewed data from 9,007 patients and found that baclofen (a muscle relaxant), duloxetine (a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor or SNRI antidepressant), NSAIDs, and opiates had high levels of evidence that they were able to improve pain and disability levels [14]. However, these types of medications all require different levels of follow-up and monitoring. For the busy emergency room provider, they may not be inclined to choose a medication that requires long-term management. For the primary care provider, they may have restrictive prescribing practices and be unable to prescribe opioids. In some states, gabapentin is also a controlled substance and may be restrictive as to who may prescribe or manage it.

So in short, it’s not clear at this time what evidence-based medication management looks like in the context of chronic low back pain. In this short article we have discussed three different credible resources that all recommend varying opinions, with the only consistency being a trial of NSAIDs, which, as we also discussed, are not without risk. For us conservative care providers, this should underscore the importance of the non-pharmacological services that we are able to provide patients in chronic pain and that there is no one “magic bullet.” This article should also help shed to light some explanation for the heterogeneity in prescribing practices and trends that we see in our own patients.

Dr. Price is a staff chiropractor at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, Wash.

References

- Lisi AJ, Salsbury SA, Twist EJ, Goertz CM. Chiropractic Integration into Private Sector Medical Facilities: A Multisite Qualitative Case Study. J Altern Complement Med. 2018;24(8):792-800. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.0218

- Zeliadt SB, Douglas JH, Gelman H, et al. Effectiveness of a whole health model of care emphasizing complementary and integrative health on reducing opioid use among patients with chronic pain. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1053. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08388-2

- Trager RJ, Cupler ZA, DeLano KJ, Perez JA, Dusek JA. Association between chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy and benzodiazepine prescription in patients with radicular low back pain: a retrospective cohort study using real-world data from the USA. BMJ Open. 2022;12(6):e058769. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058769

- Whedon JM, Toler AWJ, Kazal LA, Bezdjian S, Goehl JM, Greenstein J. Impact of Chiropractic Care on Use of Prescription Opioids in Patients with Spinal Pain. Pain Med. 2020;21(12):3567-3573. doi:10.1093/pm/pnaa014

- Lisi AJ, Corcoran KL, DeRycke EC, et al. Opioid Use Among Veterans of Recent Wars Receiving Veterans Affairs Chiropractic Care. Pain Med. 2018;19(suppl_1):S54-S60. doi:10.1093/pm/pny114

- Corcoran KL, Bastian LA, Gunderson CG, Steffens C, Brackett A, Lisi AJ. Association Between Chiropractic Use and Opioid Receipt Among Patients with Spinal Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pain Med. Published online September 27, 2019:pnz219. doi:10.1093/pm/pnz219

- Acharya M, Chopra D, Smith AM, Fritz JM, Martin BC. Associations Between Early Chiropractic Care and Physical Therapy on Subsequent Opioid Use Among Persons With Low Back Pain in Arkansas. J Chiropr Med. 2022;21(2):67-76. doi:10.1016/j.jcm.2022.02.007

- Emary PC, Brown AL, Oremus M, et al. The association between chiropractic integration in an Ontario community health centre and continued prescription opioid use for chronic non-cancer spinal pain: a sequential explanatory mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1313. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08632-9

- Trager RJ, Cupler ZA, Srinivasan R, Casselberry RM, Perez JA, Dusek JA. Association between chiropractic spinal manipulation and gabapentin prescription in adults with radicular low back pain: retrospective cohort study using US data. BMJ Open. 2023;13(7):e073258. Published 2023 Jul 21. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2023-073258

- Price MR, Cupler ZA, Hawk C, Bednarz EM, Walters SA, Daniels CJ. Systematic review of guideline-recommended medications prescribed for treatment of low back pain. Chiropr Man Therap. 2022;30(1):26. Published 2022 May 13. doi:10.1186/s12998-022-00435-3

- Williams CM, Maher CG, Latimer J, et al. Efficacy of paracetamol for acute low-back pain: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9954):1586-1596. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60805-9

- Saragiotto BT, Machado GC, Ferreira ML, Pinheiro MB, Abdel Shaheed C, Maher CG. Paracetamol for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(6):CD012230. Published 2016 Jun 7. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012230

- Yang J, Bauer BA, Wahner-Roedler DL, Chon TY, Xiao L. The Modified WHO Analgesic Ladder: Is It Appropriate for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain? J Pain Res. 2020;Volume 13:411-417. doi:10.2147/JPR.S244173

- Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Eschweiler J, et al. The pharmacological management of chronic lower back pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2021;22(1):109-119. doi:10.1080/14656566.2020.1817384